Escorting the System

- Dr Sarah Ireland

- Sep 7

- 4 min read

Larrakia Country, Northern Territory, 7 September 2025

Photo credit: Sarah Ireland. Boarding a plane on the Wadeye airstrip.

While our partnership project is trying to return childbirth services to the island, the recent announcement that all pregnant women in the Northern Territory will now be automatically approved for an escort is such welcome news!! To appreciate the significance of this reform, it’s worth looking back.

Evacuation as Routine Practice

In the early 1980s, evacuation for birth became routine. Women were flown to Darwin or Gove Hospitals, even though clinics in some communities like Galiwin’ku were equipped with birthing rooms, staffed by nurses and Aboriginal Health Workers experienced in clinical midwifery care.

By 1982, records show that only 31% of women from Galiwin’ku gave birth locally. A further 6% birthed at camp. The remaining women traveled out of community - most without another Yolŋu woman beside them.

A medical journal from the time noted, almost approvingly, that these women “acquit themselves well in labour despite the fact that in hospital they have no other Aboriginal women with them.” (Watson, 1985 pg.793)

While the practice may have been driven by a desire to improve biomedical outcomes, the impact was profound: cultural authority in childbirth was disrupted, Yolŋu knowledge systems sidelined, and women’s autonomy diminished. These impacts were felt across many other remote First Nations communities too.

Escorts and the Travel Scheme

Childbirth travel came to be funded through the Patient Assistance Travel Scheme (PATS). Originally part of a federal program, PATS shifted to Northern Territory administration in 1987, with guidelines formalised by 1998. These guidelines covered expenses for “obstetrical confinement” but did not guarantee that a woman could travel with support.

Over time, the scheme has come to include escorts - usually a family member – which are approved only under certain strict circumstances to accompany women. They stay in hostels together, waiting for labour to begin. The allowance is minimal, just $60 per person per night which puts pressure on the quality and availability of good accommodation. Escort approval has never been automatic and often inconsistently applied.

Advocates have been escorting the health system itself — pressing it to walk differently, to carry care with more humanity, and to acknowledge the authority of First Nations perinatal knowledge systems.

Clinicians and researchers consistently have called for change, pointing to harms ranging from the physiological stress on women to the moral injury experienced by staff. Yet for decades, the system kept only money at the center of decision-making, not women and babies.

How wonderful it is to finally see PATS reform that centers the well being of mothers and babies during the challenges of birthing away from home and community.

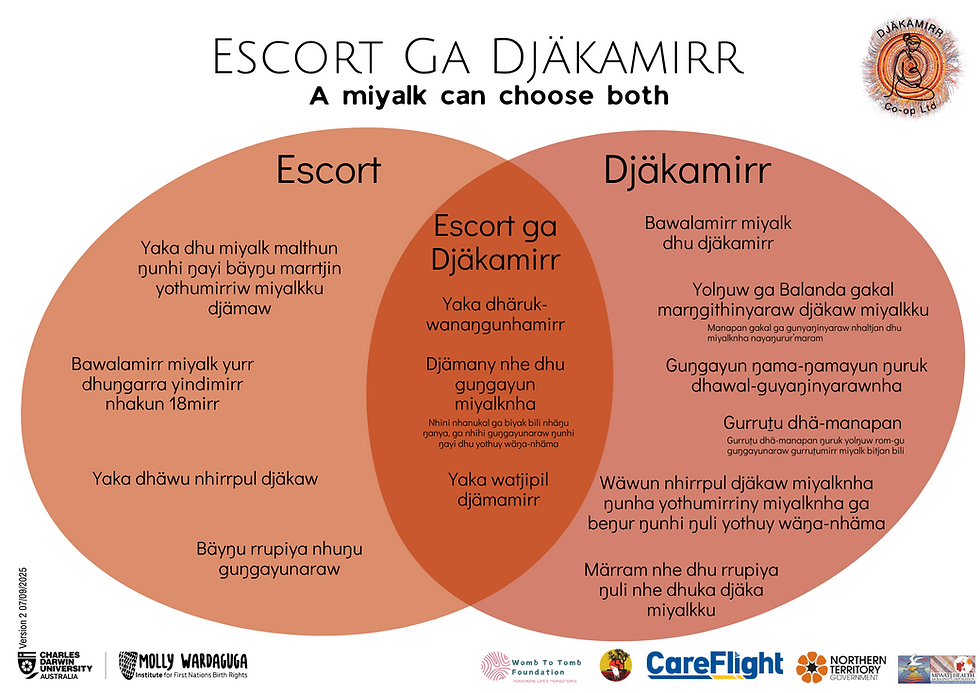

Distinct but Connected: Escort and Djäkamirr

The role of the escort is important, but it is not the same as that of a djäkamirr. Escorts provide company and practical help during travel and hospital stays.

Djäkamirr, by contrast, are skilled cultural caretakers. They walk with women across the entire pregnancy journey, drawing on both Yolŋu and Balanda knowledge, and skills gained through accredited vocational education training. They are remunerated for their work and, crucially, they carry the responsibility of re-anchoring maternity care within Yolŋu systems of law, kinship, and knowledge. We also know that continuity of care across this whole journey will improve biomedical outcomes and women's experiences.

Where escorts help reduce the loneliness of birth away from home, djäkamirr actively counter epistemological violence — reclaiming and re-centering First Nations perinatal practices.

A Step Toward Dignity

With the new PATS guidelines, women in Galiwin’ku can now travel with a nominated family member. Through our research partnerships, many will also have the support of a kinship-matched, skilled djäkamirr. This change is a step toward restoring dignity. It begins to humanise a system that, for too long, dismantled Yolŋu knowledge and authority.

It is sobering to reflect that while childbirth was being removed from Galiwin’ku in the 1980s, Inuit women on the Hudson Bay coast of Canada were opening the Puvirnituq Maternity in 1986.

Their story continues to inspire other remote Inuit communities and resonates with Galiwin’ku’s own aspirations to bring birth back to the island under Yolŋu control.

Our journey towards these goals is far from finished. But today we pause to acknowledge and celebrate that Yolŋu women have been afforded more choice, support, and dignity in their pregnancy and childbirth journey.

Learn more from these references

Hodnett, E. D., Gates, S., Hofmeyr, G. J., Sakala, C., & Weston, J. (2013). Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), CD003766. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub5

Ireland, S., Belton, S., McGrath, A., Saggers, S., & Narjic, C. (2015). Paperbark and Pinard: A Historical Account of Maternity Care in One Remote Australian Aboriginal Town. Women and Birth, 28(4), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.06.002

Northern Territory Department of Health – Northern Territory Patients Assistance Travel Scheme (PATS), 1990

Northern Territory Department of Health – Patient Travel Scheme Guidelines, 1998

Northern Territory Department of Health – Patient Travel Scheme Guidelines, 2003

Northern Territory Government. (n.d.). Patient Assistance Travel Scheme: What you can claim for. Northern Territory Government. https://nt.gov.au/wellbeing/health-subsidies-support-and-home-visits/patient-assistance-travel-scheme/what-you-can-claim-for

Rural Health Alliance – Patient Assistance Travel Scheme Fact Sheet and Guide 2025

Watson,D, (1985). Obstetrics at Galiwin’ku. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Aug 84, Vol 91, pp.791-796.

Comments